Joey Cofone is an award-winning designer and entrepreneur, the founder of design house Baronfig, and author of The Laws of Creativity. Cofone has designed over 125 products from concept to launch, and his work has been featured in Fast Company, Bloomberg, New York Magazine, and many other publications. His website is www.joeycofone.com.

What sparked your early interest in creativity and design, and how has your career path evolved over time?

I will never forget the moment when I understood the power of creativity. I was seven, in first grade, and sitting at my desk. I really had to pee. For whatever reason, the teacher wouldn’t call on me. My hand was in the air, swinging. But no response. If I didn’t act quickly, I was going to go in my pants.

With few tools at my disposal, I grabbed my pencil and wrote “I HAVE TO PEE” on a sticky note. Then slapped it on my forehead. My teacher looked my way, paused for a moment, and then said “Go.”

That’s the exact moment I discovered there were no hard rules.

Since then, I’ve constantly worked to develop my creative skills—writing, drawing, speaking, ideating—as well as my ability to get things done. Discipline became the foundation for which everything was built.

Today, I still use all those skills on a daily basis.

You studied literature and philosophy before pivoting to graphic design. How did those early studies in the humanities shape your approach to design and creative thinking?

I didn’t plan it, but I ended up going to university for eight years straight. Including summers.

My first study was literature and philosophy because I love learning from the best minds across human history. It just so happened that my fourth year ended during the 2008 financial crisis. There were few jobs in literature and philosophy to begin with—so you can imagine the wasteland of opportunities I found myself in.

So what did I do? Why, drink too much beer, of course. Which, unbeknownst to me at the time, would be one of the best things I ever did. I’ll explain.

After realizing the state of the job market, I bought a six-pack of beer and drank them all in my dorm room. As expected, I ended up pretty loopy and, in my adjusted state of mind, decided it was a great idea to draw on my walls with permanent marker.

I woke up in a haze the next morning. My room was covered with drawings and doodles from floor to ceiling. Before I could figure out how I felt about the previous night, a friend visited. She stopped in the doorway, taking in my creative explosion. After a few moments, she said, “These are really good. You should go to art school.”

So I did.

I spent the next four years exploring graphic design, filling it up with all the brilliant ideas I’d learned the four years prior.

When did you first realize that creativity wasn't mere “magic” but rather something that could be understood, taught, and systematized? And what led you from that point to deciding to write The Laws of Creativity?

It came from a simple thought: if creativity were magic—as in some mysterious, impossible-to-understand force that may or may not show up—then how are millions of people in creative jobs showing up to work every day and fulfilling their responsibilities?

The answer can only be: creativity isn’t magic.

Which begs the question—then what is it?

And that led me down the path to understand creativity, something that I had innately mastered but consciously misunderstood. This isn’t uncommon, either. Think of it this way: there have been countless successful and skilled musicians—such as Jimi Hendrix, Taylor Swift, Michael Jackson, and many more—who understand music innately, but can’t read sheet music or tell you the science behind why two notes harmonize so well.

Creativity is the same. Many can play, but few can read the sheet music.

Your book contains 39 laws of creativity, inspired by the stories of many iconic creators across history. Is there a common thread between all the people who inspired these laws? What drew you to them?

Absolutely. Rebellion and creativity.

Every person who has ever made an impact has rebelled against someone or something (an idea, an expectation, a societal norm, a tradition, etc.) and used their creativity to do it. All thirty-nine chapters begin with a true story that illustrates the law being examined.

Sprinkled throughout the book, you’ll also encounter a few of my personal stories. Like the primary stories, they often feature a rebellious moment in which I leveraged my own creativity to achieve a goal.

You organized the laws in the book into three sections: Foundation, Process, and Excellence. Could you walk us through the process of recognizing such laws and structuring them?

Thank you for using the word “recognizing.” As I say in the introduction, I didn’t create these laws, I merely uncovered and organized them. They are fundamental truths of human nature. Of society. Of creating by speaking from our depths and being honest with ourselves and those we create for.

Foundation contains a set of laws that set the stage for being able to create at all. It’s a short set of laws that point out the importance and effects of our beliefs on our ability to be creative. You could be the smartest person in the world, but if you don’t operate from these laws, you’ll never create anything worthwhile.

Process is a set of laws that follow you through every step of the creative process, from ideation to iteration to publication. It’s a chronological, step-by-step guide to the actual process of creating something.

Excellence is my favorite series of laws. I’ve been operating Baronfig for over a decade, and I’ve had the unique pleasure of personally working with some of the most beautiful minds today: bestselling authors, award-winning visual artists, even professional athletes. In doing so, it’s become apparent that they all see the world through a very similar lens—they’re operating by the same laws. These are collected here in this final section, and, if followed, help the reader transcend into something far greater than they ever expected.

Which of the 39 laws of creativity would you consider the most fundamental for writers to keep in mind, and why?

This is a very tough question, as the thirty-nine laws are all enacted in any creative project. If I had to choose one that I think would be interesting to someone reading right now, I’d say the Law of Specificity:

Make for yourself and you will appeal to many. Make for many and you will appeal to none.

Most of us write because we love to read. But I think it’s easy to forget that we should often be our own core reader. The more you write about the things you like, regardless of how niche, the more you attract others who see the unique human behind the creation.

What did the creative process of writing this book teach you along the way? Did your own writing experience inform some of the principles you have shared? Or, on the other hand, did it change your mind on “laws” you had planned to include?

Ah! I see the word laws is in quotes. Do you wonder if these laws are, in fact, laws? I urge you to read the book and find out for yourself. Your dubiousness is expected. That’s why I titled the book as such; I knew creatives would bristle at the idea that their magic isn’t magic. My book is a white glove to their cheek, a challenge to prove me wrong. A battle to the creative depths.

As for my writing process, it was extremely fluid. Here’s the data for my first draft, which ended up being about ninety percent of the final book:

- 199 writing sessions

- 414.7 average words per session

- 82,527 total words across 291.8 pages

- 8 months to completion

I somehow stumbled on the perfect process for me: I outlined the table of contents. Then I wrote the introduction. Then I wrote each chapter, first doing the research and then collecting my thoughts in prose. For each chapter, my wife read it out loud, and we both reacted to its ideas, writing, and overall presentation.

There’s a bit of detail I’m leaving out, such as the way I actually organized the book that made it so easy to write, but perhaps that’s something I’ll one day share in a deeper dive on process.

And yes, the entire thing became a meta-experience as I used the laws while writing about them.

You talk about the creative process as having distinct phases: get inspired, research, iterate, and finalize. How do you know when to move from one phase to the next?

Great question. This is something a lot of folks get caught up on. Process is the largest section of my book; there are a host of nuances to moving through a creative endeavor. Rather than attempt to answer here the different reasons why one can or should move between phases, I’m going to address the foundational challenge that affects the entire process:

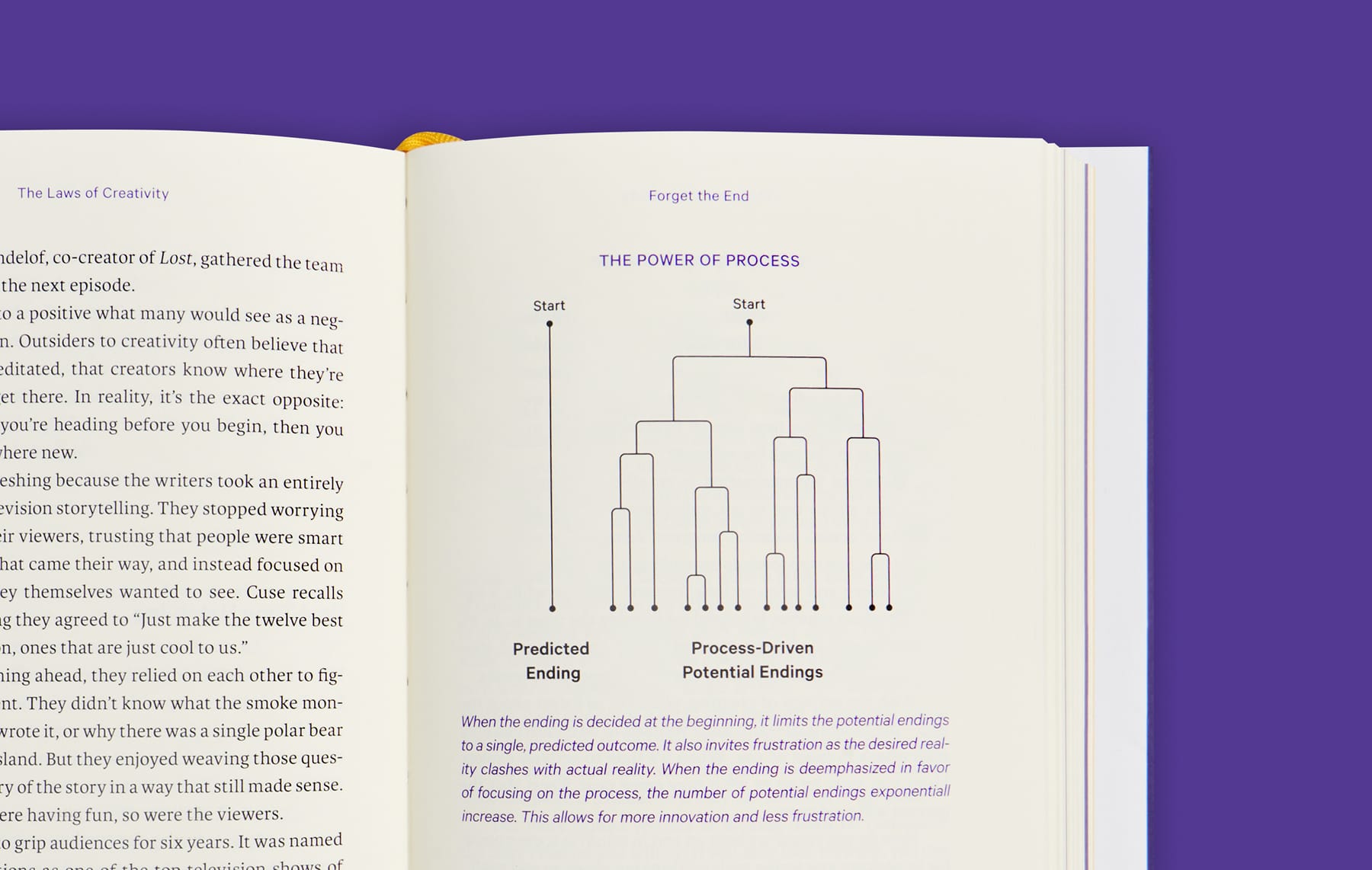

Most mistake the creative process as a linear one, when it’s far from it. In actuality, we move forward a phase when we think we have something interesting or exciting, and we move backward when we get stuck or find something lacking. And, to make matters even more challenging, often these phases are happening simultaneously, as if in parley with one another.

So if you want to move to the next phase, just go for it. You’ll know soon enough if you need to retrace your steps or if you’ve uncovered something worthwhile.

Is there one law that feels deeply personal to you and that you live your creative life by? Do you believe in a one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to creativity?

I’d say they’re all personal on some level—each one is required to create, and I create every day—but there is one that resonates most with me: The Law of Growth. It states:

Learning has no limits. Don’t be content to master one skill and neglect others. Without diversification, your strengths can turn into weaknesses. Commit to being a student for life.

Perhaps it’s just because I love to learn. Or because this particular chapter features one of my favorite stories in the book.

I do not think there’s a one-size-fits-all approach to creating. But I do believe (obviously) there’s a set of laws that govern creativity. For example, soccer/football has a singular set of rules that every player must adhere to. But there have been countless ways to play the game; incredible players have used all sorts of styles, preferences, strengths and weaknesses. The Laws of Creativity are like the rules of the game. And we are the players.

How have you relied on these laws to get through challenges in your everyday life?

One of my early readers, upon finishing the first full draft, told me my book isn’t really about creativity—it’s about life. He compared it to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, saying creative process is a metaphor for a life well lived.

I think the first section—Foundation, or the Laws of Mindset—builds up a set of beliefs that not only help you be more creative, but also help you live better. These laws put forth ideas about expression, self-awareness, play and discipline, and more. All of which serve you on a daily basis.

So yes, these laws help me get through all sorts of challenges, both personal and professional, creative and non-creative.

You wrote the entire book in Ulysses on your iPad. What drew you to Ulysses, and how did it fit into your writing workflow?

I never thought I’d write a book on an iPad. But Ulysses was certainly the only way I was going to do it, whether tablet or laptop.

At this point, I’ve been using Ulysses for more years than I can count. Probably since the software was first introduced. As a designer, I love the simple, intuitive interface. As a writer, I love having just the right amount of essentials to do my best work. Most text editors are bloated with all sorts of distracting fluff that takes away from the only important thing: writing. And of those who try to forge a minimal approach, Ulysses is the only one that hits the perfect balance between usability, features, and design.

Ulysses also allows its users to easily move between laptop, tablet, and phone—which is a critical part of my process. I ended up writing my book on an iPad because I just found the experience so pure and flexible. By design, my iPad is significantly less distracting (I only keep a handful of apps on it), and I’m able to quickly snag the tablet off the keyboard’s magnetic holder to quickly read through my work. It’s just so dynamic.

If you haven’t tried Ulysses + iPad, I highly recommend it.

Why is creativity important? What do you believe to be the place of creative thinkers in the world?

A couple of years ago, this would’ve been a much easier question. But today, with AI in the mix, it’s much more challenging to see how creative thinkers fit. I’m not going to pretend to know that I know where we’ll be in a decade, or even in a year. But I can tell you this:

Creativity is the practice of ideas. Everything—and I mean everything—in our lives is a result of these ideas. Without creativity, we’d have nothing. Whether those ideas are organic or artificially developed, it takes a human to decide which are worth pursuing.

So, for now, we continue to develop our creativity to maximize our future potential.

Are there any upcoming projects you’re looking forward to exploring next?

Yes! As always, please visit Baronfig to see what we’re up to. And, if you’d like to hear about my next writing project, sign up at joeycofone.com/secret-project to be the first to know more.