Geoffrey Makstutis is an architect and works in one of the world’s largest education companies. He also writes books; the latest, Design Process in Architecture, will shortly be released with Laurence King Publishing. From having an idea for a book to its actual release, it can be a long journey. Geoffrey describes how his ideas take shape in Ulysses, how he’s handling images (his book contains a lot of them), and how copyright clearances, reviews and translations contribute to the complexity of the whole process.

Please tell us something about you and what you are working on.

Originally from the United States, for the past 28 years I have lived and worked in London. I am an architect, educator and author. I studied architecture in the United States and the United Kingdom; with most of my professional practice being within different firms in the UK. I’ve worked on projects; ranging from small residential schemes to large cultural institutions, in the UK, US and Far East. In 2004, I became a full-time academic; running the architecture program for a UK university. Since 2016, I have been working for one of the largest education companies in the world, developing vocational qualifications related to construction, art & design and creative media production.

What is writing for you — a profession, a hobby, or a calling?

Writing plays multiple roles in my life. My professional work involves a great deal of writing; ranging from producing reports to developing qualifications to creating training materials. When my day-to-day work was purely academic, I did a good deal of research; so I was involved in writing research proposals and research reports. In addition, I was often reviewing and writing academic policy information.

Throughout my professional career, I have also written because it is something I enjoy — a passion. I enjoy the process of research, formulating a position and then developing this into something that (hopefully) makes sense to others. I find that there is something therapeutic about the actual process of writing. It can take time to get into the ‘flow’, but once it happens, there is a sense of release as the words come out on the screen. I can easily lose hours, without noticing, when I am in a good writing frame of mind.

It can take time to get into the flow, but once it happens, there is a sense of release as the words come out on the screen.

While Ulysses was, initially, a tool I used just for my own writing. I now use it in my professional work as well. When I have need to produce something longer than a couple of pages, I’ll start a project in Ulysses. The ability to export to Microsoft Word means that Ulysses can help me achieve different types of projects.

In a couple of days, your new book Design Process in Architecture will be released with Laurence King Publishing. Could you please explain what the book is about?

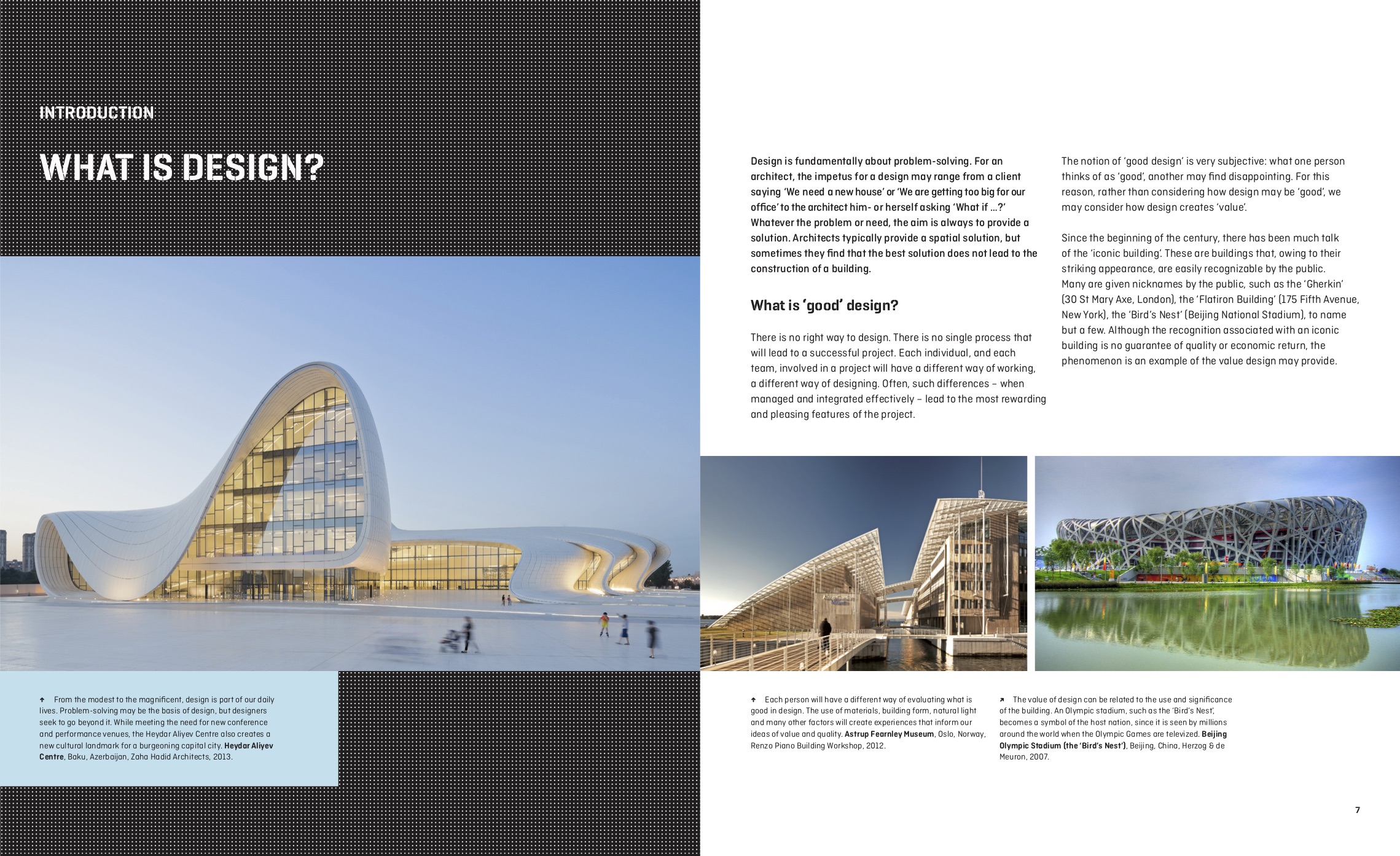

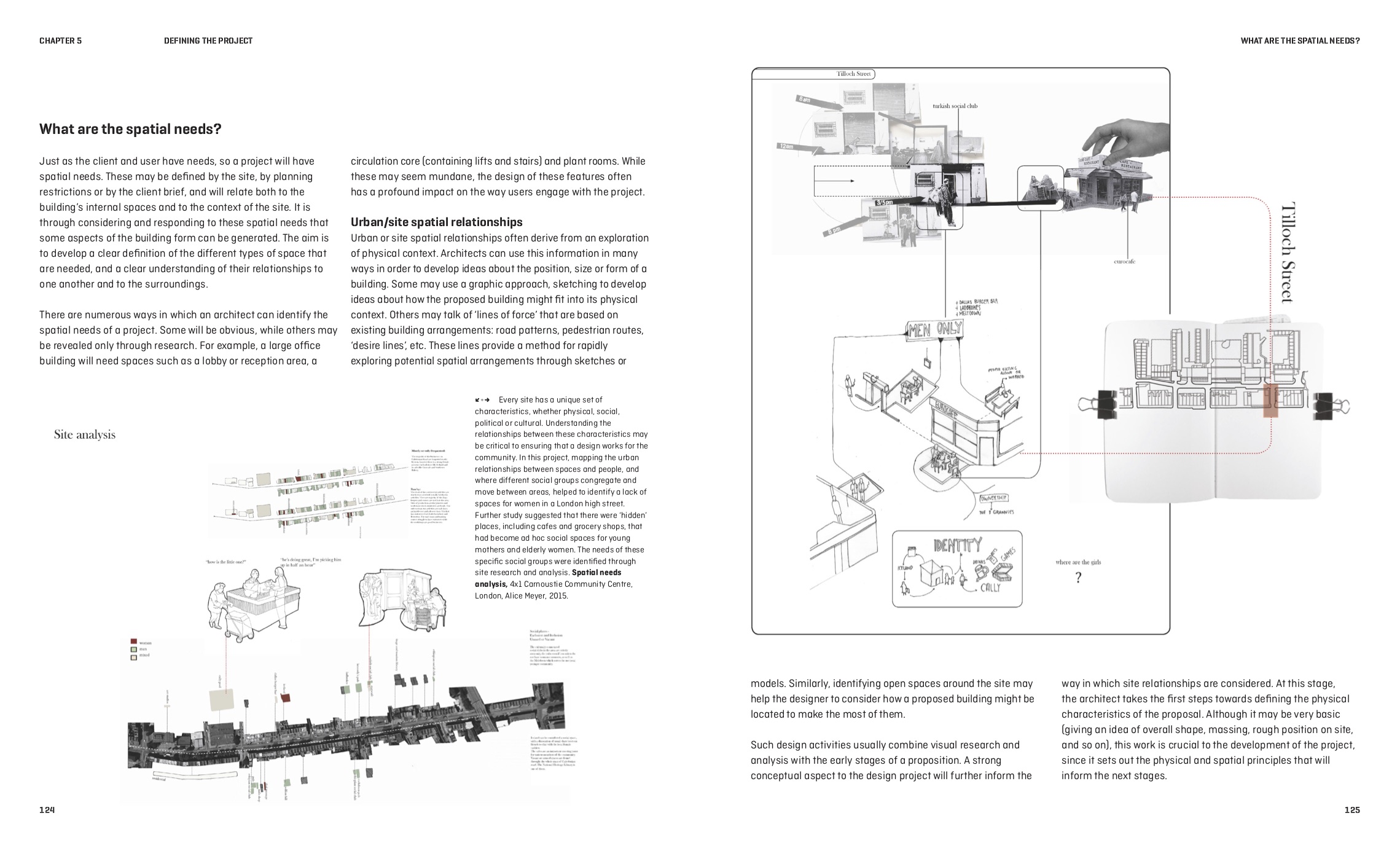

For students beginning to study architecture, there are many different ways in which to address design. One of the challenges is to find one’s own approach. So, one aspect of Design Process in Architecture is to explore different approaches to design, through a range of projects. The book explores both abstract models of the design process (looking at the way different approaches move through different steps in the process) as well as concrete examples through the detailed exploration of different projects, and interviews with architects.

In addition, there can be a tendency for students to see design as an activity that takes place at the start of a project, and ends when the project moves into a more technical phase. The book also aims to show how design is a process that continues throughout a project life-cycle. The nature of the design activity changes, but there are design decisions during all stages of a project. To illustrate this, one chapter of the book follows a single project from start to completion.

In addition, there can be a tendency for students to see design as an activity that takes place at the start of a project, and ends when the project moves into a more technical phase. The book also aims to show how design is a process that continues throughout a project life-cycle. The nature of the design activity changes, but there are design decisions during all stages of a project. To illustrate this, one chapter of the book follows a single project from start to completion.

Please describe how you have used Ulysses to write the book.

Ulysses is really my ‘toolbox’ for writing. I start by creating an outline in a single sheet. To this, I start adding notes and ideas to the different levels in the outline. When the outline starts to become a bit ‘fleshed-out’, I will split it into separate sheets (using the ‘Split at Selection’ feature). I will continue in this manner until I start to have clearly defined chapters and sections.

I tend to split, glue and merge sheets quite a lot. I split in order to move sections of text into different configurations; or even different chapters. In some cases, I will split a sheet down to individual paragraphs, so that I can consider very fine-grained ways of re-arranging the flow of ideas. As things get more definitive, I’ll glue or merge sheets together. I find this a useful feature, as it allows me to quickly try out different ways of presenting information.

As someone with a design training, I have a tendency to get caught up on the visual or graphic presentation of things. When using traditional word-processors, I can find myself wasting a good deal of time changing fonts, adjusting paragraph styles, etc. All of which means I’m not actually getting any writing done. So, the Markdown nature of Ulysses and the ability to work ‘distraction-free’ is of great benefit to me. When I feel the need to really focus, I’ll put Ulysses in full-screen mode, with none of the sidebars and just concentrate on the words. I think this has probably been one of the most productivity-boosting features of Ulysses.

As probably most books about architecture, yours contains a lot of photos, sketches and plans. How did you handle these while writing?

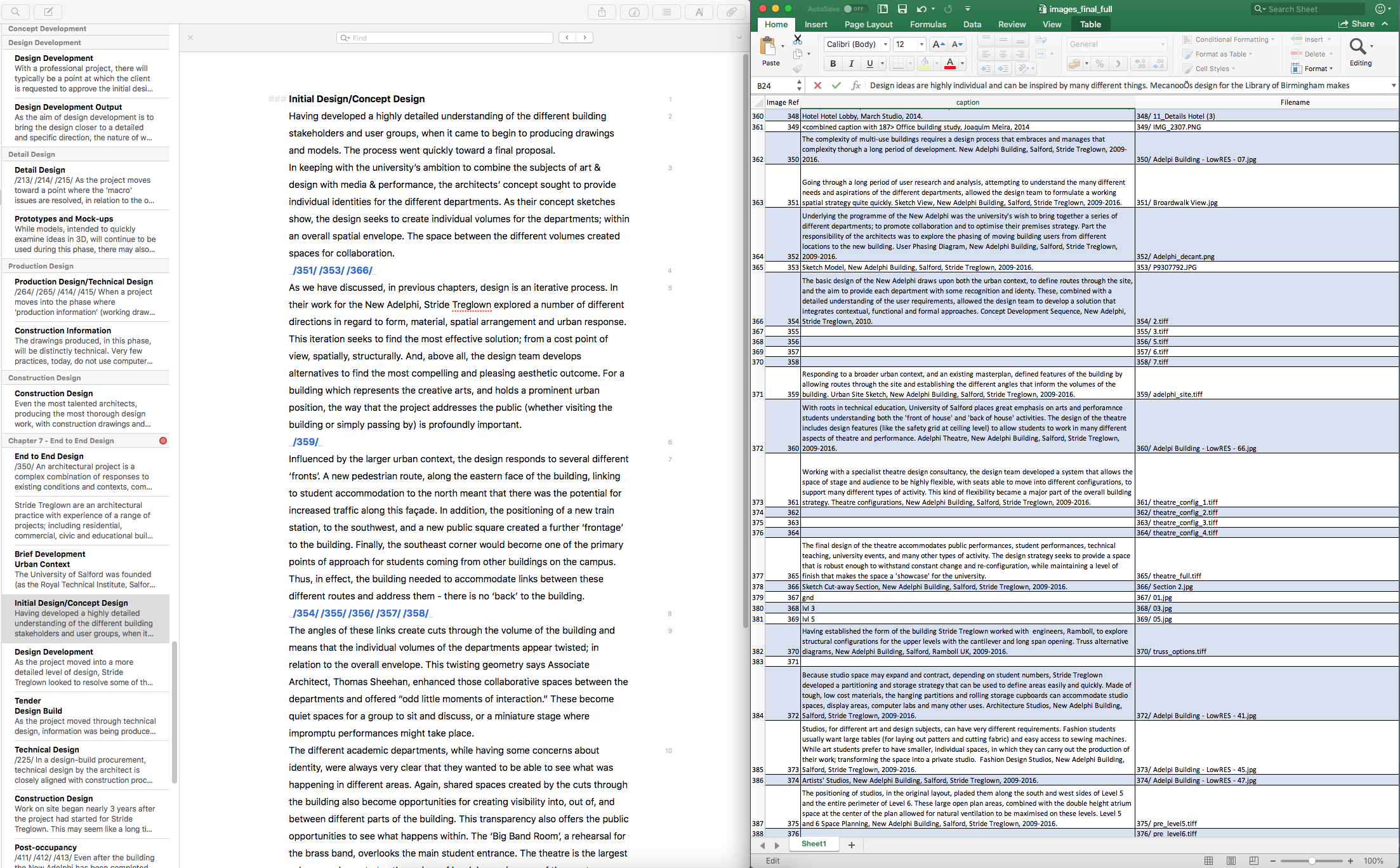

Images are one of the areas where I still find I need to jump outside of Ulysses. Design Process in Architecture has about 350 images (photographs, architectural drawing, diagrams), and nearly every one of them is specific to something that appears within the body of the text and will have a caption. In addition, each of these images needs rights (copyright) clearance and (in some cases) fees paid to photographers or agencies. While I’d love to be able to manage all of this through Ulysses, it becomes very complex. So, I make use of a spreadsheet where I can track each image, filename, architect, photographer, rights clearance status, etc.

What makes all of this more complicated, is that in some cases I might have an image in mind while writing and then find that I cannot use that image and have to replace it with something else. This could be due to the cost of the photographic rights or because we cannot get a version that is suitably high-resolution. So, I am often swapping images in and out of the book.

Further, because the book has to fit within an overall design scheme that the publisher will be developing, I don’t know exactly where the image will appear or how large an image the book designer might choose to use. Thus, I need to indicate roughly where the images should appear; within the flow of the text, and then (when we have designed page layouts) I can work with the book designer to finalize size and position of each image.

So, embedding the images within the Ulysses document doesn’t really work. However, what does work is using a simple way of referencing the image numbers, from my spreadsheet, into the text. For this, I use a simple format like “/123/”. This allows me to highlight where the image will appear, in a way that the designer can quickly see when viewing the text. It also allows me a quick way of searching for where a particular image is used, and check the caption, status, etc. within the associated spreadsheet.

What is the most difficult thing about writing a book?

For me, the actual process of writing is not what takes the most time or is the most difficult. Rather, it is the sheer amount of time that it takes to get from an initial idea to a published book.

For the type of books that I’ve written, which are generally classed as textbooks, there is a great deal of reviewing that is done during the process. At the start, the initial outline is reviewed by the publisher; as well as selected academics in the US and the UK. Later, when the initial manuscript is completed, this is also reviewed by academics. This allows the publisher to ensure that the book will have a clear market within tutors and students. However, it adds a good deal of time to the overall process; and can sometimes lead to considerable re-writes.

The other thing that always takes more time than expected is getting all of the images, in high-resolution, and dealing with all of the copyright clearances. In most cases, architects are very generous with images from their own libraries, but you will also find that some image rights are held by the photographer or the photographer’s agent. This can lead to some fairly lengthy negotiations, with contracts going back and forth. With photographs of historic buildings, you can also find that you are dealing with museum collections or specialist photographic archives, which have their own set of challenges.

The more I write, the more I learn that there is a kind of partnership between author and editor.

The final piece of the time it takes to achieve publication is languages. Design Process in Architecture will be published in English, Spanish and Chinese. As the rights to the different languages are with different publishers (the UK publisher enters into separate contracts with other publishers for each language), this can add more time. Each of the separate publishers wants to ensure that the book is released at the same time so that they don’t lose sales to the other language versions. While this can add time, I have to admit, it is really wonderful to see the different language versions.

The one aspect of writing that I have had to learn to deal with is responding to editors’ suggestions. I can well imagine that many authors feel that the manuscript they send to the publisher is the best it can possibly be — there is nothing more that can (or should) be done. When I first started writing professionally, I struggled with responding to editors’ comments, feeling that they were asking me to destroy something I’d worked so hard to perfect. However, the more I write, the more I learn that there is a kind of partnership between author and editor, and thanks to my editors, the books that have been published are better than they would have been if it had just been my singular vision.

“Design Process in Architecture” is not your first book. Are you planning to write more?

Absolutely. I’m already developing new ideas for books. I’m not yet sure what the next book will be, but I’m always developing different ideas and outlines. I don’t tend to write without having a contract, so most of my initial work is pitching the ideas to publishers. Once they agree to proceed, I will begin the research and writing in earnest.

While, to date, my published work has been non-fiction and aimed at the higher education market, I do have some fiction ideas that I’ve been exploring for a number of years. Who knows, the next book might be a novel…

What is a typical day in Geoffrey Makstutis’ life like?

Because my ‘day job’ is not as a professional writer, most of my published writing is done in the evenings and at weekends.

My typical day starts around 5:45, when the alarm goes off. I like to get up early and head into the office, as I find I can get more accomplished in the hours before others start to fill the office. After a quick breakfast, I’ll usually cycle into the office. London has become much more ‘cycle-friendly’ over the last few years. It’s about 10km from my home to office, and the 25–30 minutes are a good way to clear out my mind.

Depending on what’s happening in the office, I may spend the better part of the day working on various types of writing. Reports, policy reviews, proposals and specifications are all types of writing that I undertake in my job. Depending on the time of year, and the academic calendar, I may spend a large part of my day responding to queries from tutors; who deliver the qualifications that I develop.

Another aspect of my job is the development and delivery of training sessions for teachers. So, I may be working in Powerpoint to create a training presentation or travelling to a college (sometimes in quite distant locations) to deliver a training session.

I suppose, there aren’t many ‘typical’ days for me; as I have so many different aspects to my role.

Which other tools and apps are you using, and how do they help you?

Ulysses is found on every device I use (Macs, iPads, iPhones). While this is my writing space, often I am outputting to another format in order to take the work to a different use. In these cases, I’ll be using Microsoft Word; which is the common format for both my publisher and my office.

As I mentioned, I use Microsoft Excel to organize and track the information associated with the many images that are used in my books. I’ve tried a number of different tools; including databases and other spreadsheets, but Excel still works best; purely because it is flexible enough to be used simply.

When developing outlines, I will often start with a mind-mapping tool to quickly ‘prototype’ the key concepts and relationships between ideas. iThoughtsX is very good for this. It allows you to quickly create a mind-map and then export this in many different formats, including Markdown and OPML (Outline Processor Markup Language), which means that you can import it into Ulysses.

Since much of the writing I do for my job requires research and referencing, I use Papers 3 to manage my research sources and references. Papers 3 integrates will with word-processors; including Ulysses, and the ‘citation tool’ can be used to search through cataloged PDF documents and insert a suitable reference.

Having to keep track of so many images requires a photo management application. I’ve tried a number of different solutions, and have found that tools like Pixave or Adobe Bridge work well. I use a photo manager, in conjunction with Excel, to manage the images that I include in my books.

What else is important to keep you productive? As an example, do you work in a particular environment or follow a timely routine?

When I feel the need to really focus, I’ll put Ulysses in full-screen mode, with none of the sidebars and just concentrate on the words.

Depending on the stage of the project that I’m working on, I find different environments conducive to productive writing. When I’m researching, I like to have some music playing — usually instrumental (either classical or ambient). At this stage, I will often be scanning documents or books, rather than very focused reading, I find that some background music (or in my headphones) keeps me fluid and I don’t get lost in a single document or book.

When I’m actually trying to write, I will try to find a quiet space; which (with two children) may not be at home. I’ve, on occasion, gone to the local library to sit and write.

I will also try to avoid having other software running on my computer or iPad. I close email apps, social media, and anything else that may compete for my attention.

How did you find out about Ulysses?

I had been using different text editors, some with Markdown, when I read a review on MacStories. This was at the time that I was writing my first book, Architecture: An Introduction (Laurence King Publishing) and I was struggling with trying to find a text editor that was robust enough for writing a book, but did not force me into a very specific approach. I’d been using Scrivener, which has some great features, but I was really struggling with how much configuration was required to get it to ‘get out of the way’ and let me concentrate on writing. At the time, it took me a little while to understand how to use Ulysses effectively; but once I understood the way the app was structured it became the center of my writing process.

One of the things that have always impressed me about the Ulysses developers is how responsive they have always been to the community. I’ve seen how the application has continued to develop in response to suggestions from the users.

Thanks for the interview!